Just under a month ago Facebook switched on global availability of a tool which affords users a glimpse into the murky world of tracking that its business relies upon to profile users of the wider web for ad targeting purposes.

Facebook is not going boldly into transparent daylight — but rather offering what privacy rights advocacy group Privacy International has dubbed “a tiny sticking plaster on a much wider problem”.

The problem it’s referring to is the lack of active and informed consent for mass surveillance of Internet users via background tracking technologies embedded into apps and websites, including as people browse outside Facebook’s own content garden.

The dominant social platform is also only offering this feature in the wake of the 2018 Cambridge Analytica data misuse scandal, when Mark Zuckerberg faced awkward questions in Congress about the extent of Facebook’s general web tracking. Since then policymakers around the world have dialled up scrutiny of how its business operates — and realized there’s a troubling lack of transparency in and around adtech generally and Facebook specifically.

Facebook’s tracking pixels and social plugins — aka the share/like buttons that pepper the mainstream web — have created a vast tracking infrastructure which silently informs the tech giant of Internet users’ activity, even when a person hasn’t interacted with any Facebook-branded buttons.

Facebook claims this is just ‘how the web works’. And other tech giants are similarly engaged in tracking Internet users (notably Google). But as a platform with 2.2BN+ users Facebook has got a march on the lion’s share of rivals when it comes to harvesting people’s data and building out a global database of person profiles.

It’s also positioned as a dominant player in an adtech ecosystem which means it’s the one being fed with intel by data brokers and publishers who deploy tracking tech to try to survive in such a skewed system.

Meanwhile the opacity of online tracking means the average Internet user is none the wiser that Facebook can be following what they’re browsing all over the Internet. Questions of consent loom very large indeed.

Facebook is also able to track people’s usage of third party apps if a person chooses a Facebook login option which the company encourages developers to implement in their apps — again the carrot being to be able to offer a lower friction choice vs requiring users create yet another login credential.

The price for this ‘convenience’ is data and user privacy as the Facebook login gives the tech giant a window into third part app usage.

The company has also used a VPN app it bought and badged as a security tool to glean data on third party app usage — though it’s recently stepped back from the Onavo app after a public backlash (though that did not stop it running a similar tracking program targeted at teens).

Background tracking is how Facebook’s creepy ads function (it prefers to call such behaviorally targeted ads ‘relevant’) — and how they have functioned for years

Yet it’s only in recent months that it’s offered users a glimpse into this network of online informers — by providing limited information about the entities that are passing tracking data to Facebook, as well as some limited controls.

From ‘Clear History’ to “Off-Facebook Activity”

Originally briefed in May 2018, at the crux of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, as a ‘Clear History’ option this has since been renamed ‘Off-Facebook Activity’ — a label so bloodless and devoid of ‘call to action’ that the average Facebook user, should they stumble upon it buried deep in unlovely settings menus, would more likely move along than feel moved to carry out a privacy purge.

(For the record you can access the setting here — but you do need to be logged into Facebook to do so.)

The other problem is that Facebook’s tool doesn’t actually let you purge your browsing history, it just delinks it from being associated with your Facebook ID. There is no option to actually clear your browsing history via its button. Another reason for the name switch. So, no, Facebook hasn’t built a clear history ‘button’.

“While we welcome the effort to offer more transparency to users by showing the companies from which Facebook is receiving personal data, the tool offers little way for users to take any action,” said Privacy International this week, criticizing Facebook for “not telling you everything”.

As the saying goes, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. So a little transparency implies — well — anything but clarity. And Privacy International sums up the Off-Facebook Activity tool with an apt oxymoron — describing it as “a new window to the opacity”.

“This tool illustrates just how impossible it is for users to prevent external data from being shared with Facebook,” it writes, warning with emphasis: “Without meaningful information about what data is collected and shared, and what are the ways for the user to opt-out from such collection, Off-Facebook activity is just another incomplete glimpse into Facebook’s opaque practices when it comes to tracking users and consolidating their profiles.”

It points out, for instance, that the information provided here is limited to a “simple name” — thereby preventing the user from “exercising their right to seek more information about how this data was collected”, which EU users at least are entitled to.

“As users we are entitled to know the name/contact details of companies that claim to have interacted with us. If the only thing we see, for example, is the random name of an artist we’ve never heard before (true story), how are we supposed to know whether it is their record label, agent, marketing company or even them personally targeting us with ads?” it adds.

Another criticism is Facebook is only providing limited information about each data transfer — with Privacy International noting some events are marked “under a cryptic CUSTOM” label; and that Facebook provides “no information regarding how the data was collected by the advertiser (Facebook SDK, tracking pixel, like button…) and on what device, leaving users in the dark regarding the circumstances under which this data collection took place”.

“Does Facebook really display everything they process/store about those events in the log/export?” queries privacy researcher Wolfie Christl, who tracks the adtech industry’s tracking techniques. “They have to, because otherwise they don’t fulfil their SAR [Subject Access Request] obligations [under EU law].”

Christl notes Facebook makes users jump through an additional “download” hoop in order to view data on tracked events — and even then, as Privacy International points out, it gives up only a limited view of what has actually been tracked…

“For example, why doesn’t Facebook list the specific sites/URLs visited? Do they infer data from the domains e.g. categories? If yes, why is this not in the logs?” Christl asks.

We reached out to Facebook with a number of questions, including why it doesn’t provide more detail by default. It responded with this statement attributed to spokesperson:

We offer a variety of tools to help people access their Facebook information, and we’ve designed these tools to comply with relevant laws, including GDPR. We disagree with this [Privacy International] article’s claims and would welcome the chance to discuss them with Privacy International.

Facebook also said it’s continuing to develop which information it surfaces through the Off-Facebook Activity tool — and said it welcomes feedback on this.

We also asked it about the legal bases it uses to process people’s information that’s been obtained via its tracking pixels and social plug-ins. It did not provide a response to those questions.

Six names, many questions…

When the company launched the Off-Facebook Activity tool a snap poll of available TechCrunch colleagues showed very diverse results for our respective tallies (which also may not show the most recent activity, per other Facebook caveats) — ranging from one colleague who had an eye-watering 1,117 entities (likely down to doing a lot of app testing); to several with several/a few hundred apiece; to a couple in the middle tens.

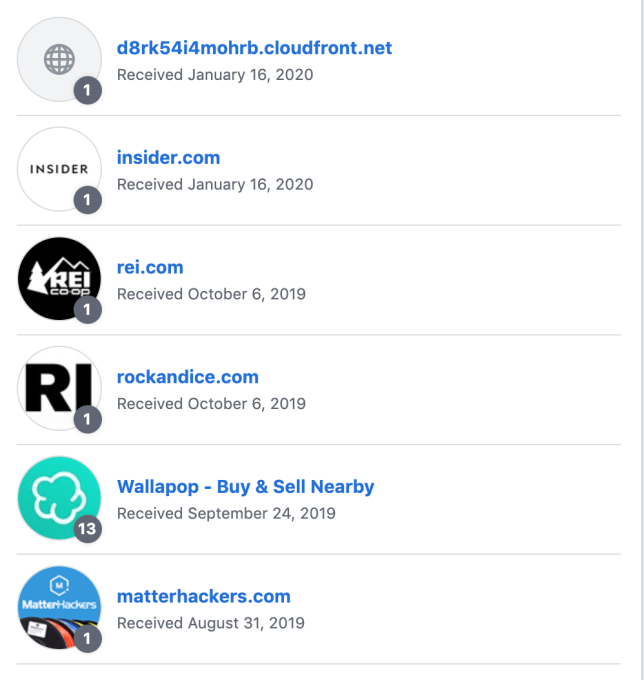

In my case I had just six. But from my point of view — as an EU citizen with a suite of rights related to privacy and data protection; and as someone who aims to practice good online privacy hygiene, including having a very locked down approach to using Facebook (never using its mobile app for instance) — it was still six too many. I wanted to find out how these entities had circumvented my attempts not to be tracked.

And in the case of the first one in the list who on earth it was…

Turns out cloudfront is an Amazon Web Services Content Delivery Network subdomain. But I had to go searching online myself to figure out that the owner of that particular domain is (now) a company called Nativo.

Facebook’s list provided only very bare bones information. I also clicked to delink the first entity, since it immediately looked so weird, and found that by doing that Facebook wiped all the entries — which meant I was unable to retain access to what little additional info it had provided about the respective data transfers.

Undeterred I set out to contact each of the six companies directly with questions — asking what data of mine they had transferred to Facebook and what legal basis they thought they had for processing my information.

(On a practical level six names looked like a sample size I could at least try to follow up manually — but remember I was the TechCrunch exception; imagine trying to request data from 1,117 companies, or 450 or even 57, which were the lengths of lists of some of my colleagues.)

This process took about a month and a lot of back and forth/chasing up. It likely only yielded as much info as it did because I was asking as a journalist; an average Internet user may have had a tougher time getting attention on their questions — though, under EU law, citizens have a right to request a copy of personal data held on them.

Eventually, I was able to obtain confirmation that tracking pixels and Facebook share buttons had been involved in my data being passed to Facebook in certain instances. Even so I remain in the dark on many things. Such as exactly what personal data Facebook received.

In one case I was told by a listed company that it doesn’t know itself what data was shared — only Facebook knows because it’s implemented the company’s “proprietary code”. (Insert your own ‘WTAF’ there.)

The legal side of these transfers also remains highly opaque. From my point of view I would not intentionally consent to any of this tracking — but in some instances the entities involved claim that (my) consent was (somehow) obtained (or implied).

In other cases they said they are relying on a legal basis in EU law that’s referred to as ‘legitimate interests’. However this requires a balancing test to be carried out to ensure a business use does not have a disproportionate impact on individual rights.

I wasn’t able to ascertain whether such tests had ever been carried out.

Meanwhile, since Facebook is also making use of the tracking information from its pixels and social plug ins (and seemingly more granular use, since some entities claimed they only get aggregate not individual data), Christl suggests it’s unlikely such a balancing test would be easy to pass for that tiny little ‘platform giant’ reason.

Notably he points out Facebook’s Business Tool terms state that it makes use of so called “event data” to “personalize features and content and to improve and secure the Facebook products” — including for “ads and recommendations”; for R&D purposes; and “to maintain the integrity of and to improve the Facebook Company Products”.

In a section of its legal terms covering the use of its pixels and SDKs Facebook also puts the onus on the entities implementing its tracking technologies to gain consent from users prior to doing so in relevant jurisdictions that “require informed consent” for tracking cookies and similar — giving the example of the EU.

“You must ensure, in a verifiable manner, that an end user provides the necessary consent before you use Facebook Business Tools to enable us to store and access cookies or other information on the end user’s device,” Facebook writes, pointing users of its tools to its Cookie Consent Guide for Sites and Apps for “suggestions on implementing consent mechanisms”.

Christl flags the contradiction between Facebook claiming users of its tracking tech needing to gain prior consent vs claims I was given by some of these entities that they don’t because they’re relying on ‘legitimate interests’.

“Using LI as a legal basis is even controversial if you use a data analytics company that reliably processes personal data strictly on behalf of you,” he argues. “I guess, industry lawyers try to argue for a broader applicability of LI, but in the case of FB business tools I don’t believe that the balancing test (a businesses legitimate interests vs. the impact on the rights and freedoms of data subjects) will work in favor of LI.”

Those entities relying on legitimate interests as a legal base for tracking would still need to offer a mechanism where users can object to the processing — and I couldn’t immediately see such a mechanism in the cases in question.

One thing is crystal clear: Facebook itself does not provide a mechanism for users to object to its processing of tracking data nor opt out of targeted ads. That remains a long-standing complaint against its business in the EU which data protection regulators are still investigating.

One more thing: Non-Facebook users continue to have no way of learning what data of theirs is being tracked and transferred to Facebook. Only Facebook users have access to the Off-Facebook Activity tool, for example. Non-users can’t even access a list.

Facebook has defended its practice of tracking non-users around the Internet as necessary for unspecified ‘security purposes’. It’s an inherently disproportionate argument of course. The practice also remains under legal challenge in the EU.

Tracking the trackers

SimpleReach (aka d8rk54i4mohrb.cloudfront.net)

What is it? A California-based analytics platform (now owned by Nativo) used by publishers and content marketers to measure how well their content/native ads performs on social media. The product began life in the early noughties as a simple tool for publishers to recommend similar content at the bottom of articles before the startup pivoted — aiming to become ‘the PageRank of social’ — offering analytics tools for publishers to track engagement around content in real-time across the social web (plugging into platform APIs). It also built statistical models to predict which pieces of content will be the most social and where, generating a proprietary per article score. SimpleReach was acquired by Nativo last year to complement analytics tools the latter already offered for tracking content on the publisher/brand’s own site.

Why did it appear in your Off-Facebook Activity list? Given it’s a b2b product it does not have a visible consumer brand of its own. And, to my knowledge, I have never visited its own website prior to investigating why it appeared in my Off-Facebook Activity list. Clearly, though, I must have visited a site (or sites) that are using its tracking/analytics tools. Of course an Internet user has no obvious way to know this — unless they’re actively using tools to monitor which trackers are tracking them.

In a further quirk, neither the SimpleReach (nor Nativo) brand names appeared in my Off-Facebook Activity list. Rather a domain name was listed — d8rk54i4mohrb.cloudfront.net — which looked at first glance weird/alarming.

I found this is owned by SimpleReach by using a tracker analytics service.

Once I knew the name I was able to connect the entry to Nativo — via news reports of the acquisition — which led me to an entity I could direct questions to.

What happened when you asked them about this? There was a bit of back and forth and then they sent a detailed response

source https://techcrunch.com/2020/02/25/facebooks-latest-transparency-tool-doesnt-offer-much-so-we-went-digging/

No comments:

Post a Comment