You may not have heard of Alan Mulally, but he’s led one of the best turnarounds in modern American business history.

As Chief Executive for nearly 8 years at Ford Motor Company, he steered the company through the Great Recession (without taking a bailout), restructured the massive corporation to get the company more focused and streamlined, returned the company to profitability, and doubled the company’s stock price during his 8-year tenure as CEO. And he didn’t do it just by cutting jobs and laying thousands of people off.

And since his days at Ford, he was rumored to be in the running to replace Steve Ballmer at Microsoft, and later, to be President Trump’s Secretary of State. He currently sits on Board at Google (now Alphabet) and the Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees.

I’m not here to write his resume or publish a biography or write a blog post about his accomplishments. I mention these accomplishments because it’s the details that led to the turnaround that most people don’t know about.

Mulally came into a bleak situation at Ford, and 2 years later the great recession began. Yet Ford was the only US automaker to not accept a bailout. And he returned the company to record profitability.

Here’s how Mulally turned the company around, and what every manager can learn from him.

From Boeing to Ford

Mulally didn’t have an automotive background before coming to Ford. In fact, he wasn’t even a Ford employee. He was CEO of Boeing Commercial Airlines, leading the turnaround in that division and making Boeing more competitive with Airbus.

So without a background in the automotive industry and with no prior work history at Ford, his first job at Ford was CEO.

Starting as CEO

In September 2006, Executive Chairman and CEO Bill Ford called Mulally to ask him to run Ford. Mulally knew that Ford was a great American company, and that he couldn’t turn down the opportunity to serve an “American icon”.

He came to Ford on a mission – to save a great American company.

So what was the first day at Ford like for Mulally, who never worked at Ford, and didn’t even drive a Ford car at the time? What situation did he find himself in?

- He drove into the company garage full of non-Ford vehicles. That’s right – all of the Ford employees that parked in the company garage didn’t even drive Ford cars. In short: they weren’t eating their own dog food.

- His finance people told him that Ford was projected to lose $17 billion in 2006.

- Ford was regionalized. There were Ford offices around the world, but none of them talked to each other. There was no synergy. None of the intellectual capability of Ford – the engineering, marketing, manufacturing – was shared.

- And the contracts with the union (known as the United Auto Workers) essentially meant that they couldn’t produce cars in the United States profitably. The workers had a good salary and great pensions, all of which meant that the cost of goods sold increased to the point where already low-margin vehicles were unprofitable.

- Their cars weren’t “best in class” and consumers knew it. The Ford brand itself was hurting. (Remember the acronym Found On Road Dead?)

- Ford Motor Company was not focused on, well, Ford. They were a “house of brands” that included Jaguar, Aston Martin, Land Rover, Volvo, and owned a 33% equity position in Mazda. Those brands were just “additions” to the Ford, Mercury, and Lincoln line of vehicles. This “family of brands” had 97 different vehicles. As Mulally says, “you can’t be world-class in 97 different things.”

The condition sounds pretty bleak doesn’t it? And nothing like the Ford of today.

And so the rebuilding began. Mulally picked apart the business, finding each problem, and fixing each one. In many cases, this simply meant making a process or operation more streamlined and efficient. Bureaucracy was removed, blaming others wasn’t allowed, and team working wasn’t just encouraged, it was the culture.

Regionalized offices that weren’t communicating were now working together. And this new cohesive team looked at the situation honestly – a projected $17 billion loss – the biggest loss in its 103-year history. That crisis allowed them to pull together around a new strategy. They developed the strategy together by focusing on the Ford and Lincoln brand (Mercury was later discontinued), and producing the entire family of vehicles (cars, utilities, trucks) to be produced profitably and, as Mulally frequently says, best in class.

Everyone pulled together on this new plan and began executing. And they were going to do it all as one team. That’s what Mulally emphasizes – creating a plan, sticking to it, and working together as a team. Everyone is accountable to each other, and they help each other out when necessary.

The Plan to Turn Around a Company – On Four Bullet Points

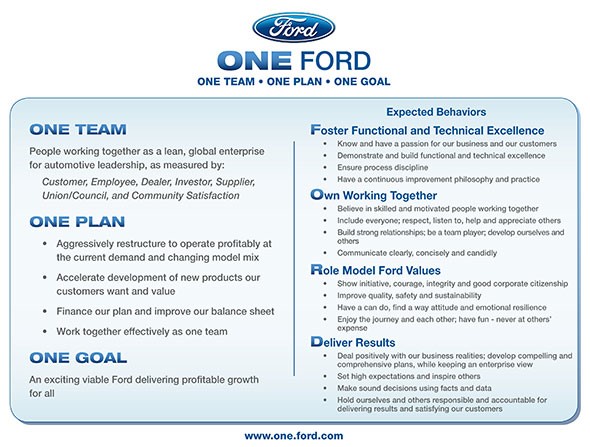

The new plan included these four bullet points:

- Aggressively restructure to operate profitably at the current demand and changing model mix

- Accelerate development of new products our customers want and value

- Finance our plan and improve our balance sheet

- Work together effectively as one team

Mulally printed it on wallet cards and distributed them to every Ford employee. Business plan on one side of the card, behaviors they expected on the other side.

He mentioned the bullet points constantly in meetings and with the press. And if you were around him enough, you’d likely be able to recite the four bullet points in your sleep.

Journalists covering the auto industry and Ford were tired of hearing it. But Mulally sticks to plans, even if people are tired of hearing them. If the goals of the plan aren’t achieved, he will continue to bring them up.

Listening to Your Critics

Every prominent company has their fair share of critics. Ford wasn’t any different. The Ford brand was severely damaged. The public viewed Ford vehicles as unreliable, with many referring to Ford with the acronym Fix Or Repair Daily. And Consumer Reports ranked them as one of the most unreliable car brands.

So what did Mulally do?

He met with Ford critics, namely he took his team to meet with Consumer Reports, who were one of the top critics of Ford vehicles.

Mulally and his team traveled and met with Consumer Reports product testers and discussed every Ford model. Product testers were critical. Mulaly didn’t argue with them or try to convince them otherwise. Instead, he used the trip to listen and understand their complaints. Mulally was grateful for the “unvarnished feedback” from the product testers.

A lot of companies live in silos and protect themselves from outside feedback. They make products without consumer input, and don’t talk to customers when they’re improving products or features. They build things nobody wants. Or worse, they’ll build something unreliable. That’s the fastest way to damage your brand.

Instead, take a lesson from Mulally. Find your legitimate critics (the ones who want you to succeed, but will give you a fair assessment) and listen to their criticism. Take it to heart and you’ll end up improving your product and processes.

The Weekly Business Plan Review Meeting

Mulally is an engineer by training. That engineering mentality means that he likes numbers. He likes to say that “the data will set you free”.

Data doesn’t lie and it doesn’t spin. It’s just facts that cannot be argued. And because of this, it’s great for showing progress and holding people accountable. Everything his executives managed could be deciphered down to numbers.

This data was used during the weekly Business Plan Review (BPR) meetings. These meetings, which took place every Thursday morning, brought Ford executives from around the world to discuss their departments and the progress they’re making on the business plan.

Bryce Hoffman, author of American Icon, explains the meetings:

Mulally’s management system, which he developed at Boeing, set clear and measurable goals for every aspect of the business. Each executive was required track their division or department’s progress against those plan goals and present it at a weekly “Business Plan Review” meeting.

The data was presented without explanation or excuses. It was also color-coded. Anything that was on plan was green, anything that was off plan was red and anything that was in danger of becoming red was highlighted in yellow.

Any issues identified in these sessions would be dealt with in a follow-up meeting known as a “Special Attention Review.” Here, discussion was allowed—but not recriminations or personal attacks. Mulally would say, “So-and-so has a problem, but he isn’t the problem. Who can help him fix it?” But this weekly return to the numbers also allowed him to enforce accountability.

Here’s what every manager can learn from this:

How do you measure progress against your plan? Does your team know the progress? Are they working together and helping each other when necessary? Many companies like Google and Intel like to use the Objectives and Key Results framework to create goals and track them.

Creating a plan is great, but most organizations and teams don’t stick to it over a long enough time period. They hit the first road bump against the plan, and end up leaving the plan altogether.

As Mulally says, “We never give up on the plan. A plan is going to be the innovator for us to find new ways to find more opportunities to meet the plan and mitigate the risk. So it’s the all-time encourager of us to use our innovation to find solutions to allow us to deliver the plan rather than to give up.”

Working Together as One Team

“Working together” sounds pretty trite, doesn’t it?

It’s an overused term for executives, managers, and coaches. And lieutenants of those in management typically roll their eyes when they hear it from their superiors.

Yet Mulally didn’t just say, “we have to work together”. He created a culture of teamwork.

Before he came to Ford, there was infighting and elbowing among executives. Forbes described the culture Mulaly came into as, “Sharp elbows, fierce loyalties, and frequent turf battles were hallmarks of Ford’s management culture: The tough guys won.”

In response to this toxic culture, Mulally created the “One Ford” mantra. The wallet-sized cards were handed to every Ford employee and the weekly BPR meetings got all the executives on onboard and helping each other when they needed it.

During those BPR meetings, each executive brought an employee from his or her department to sit in on the meeting. And they don’t remain silent, sitting like students in a classroom. They are required to listen and give feedback.

Mulally and his executives often ask these employees for their thoughts and reflections on what is being discussed. Mulally says:

“We introduce the guests, who sit behind the team member that invited them, and we ask them for their reflections and thoughts. The guests might be an engineer or someone from down on the factory floor. So, all this data is flowing up, but then all the results are also flowing down. It is going back and forth every week at these meetings. And at the end of the meeting, the comments you hear from the guests make your eyes water. They say, ‘My gosh, this is so big, so vast. We’re in every country. I want to contribute to the plan as soon as I get back.’ I have heard many guests say that.”

Bringing the “lower-level” employees to the executive boardroom probably doesn’t happen at most of the world’s biggest companies. But Mulally understood how valuable these people are – and how the people “working the floor” and meeting one-on-one with customers and being hands on with the product can provide feedback that most executives cannot. This feedback inspires executives and the employees themselves. This sense of teamwork inspires everyone in the company to deliver results.

Understand the Value Proposition of the Company

What are you in business for? How do you make people’s lives better? How is the world better off because of your company? That’s what a value proposition should answer.

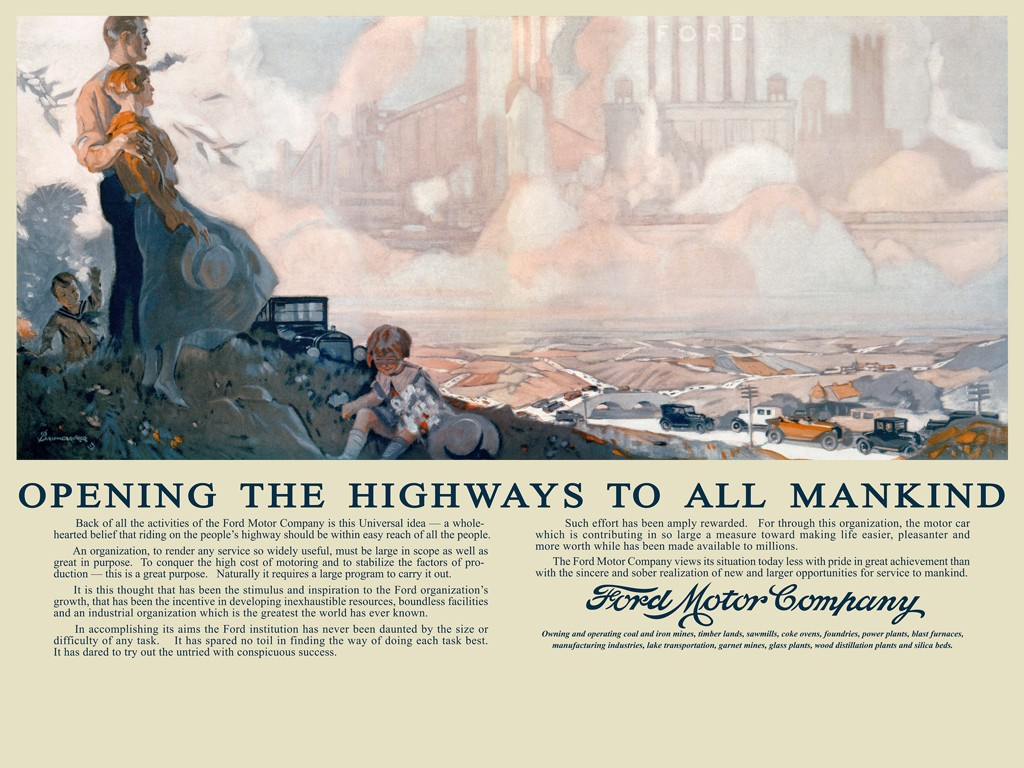

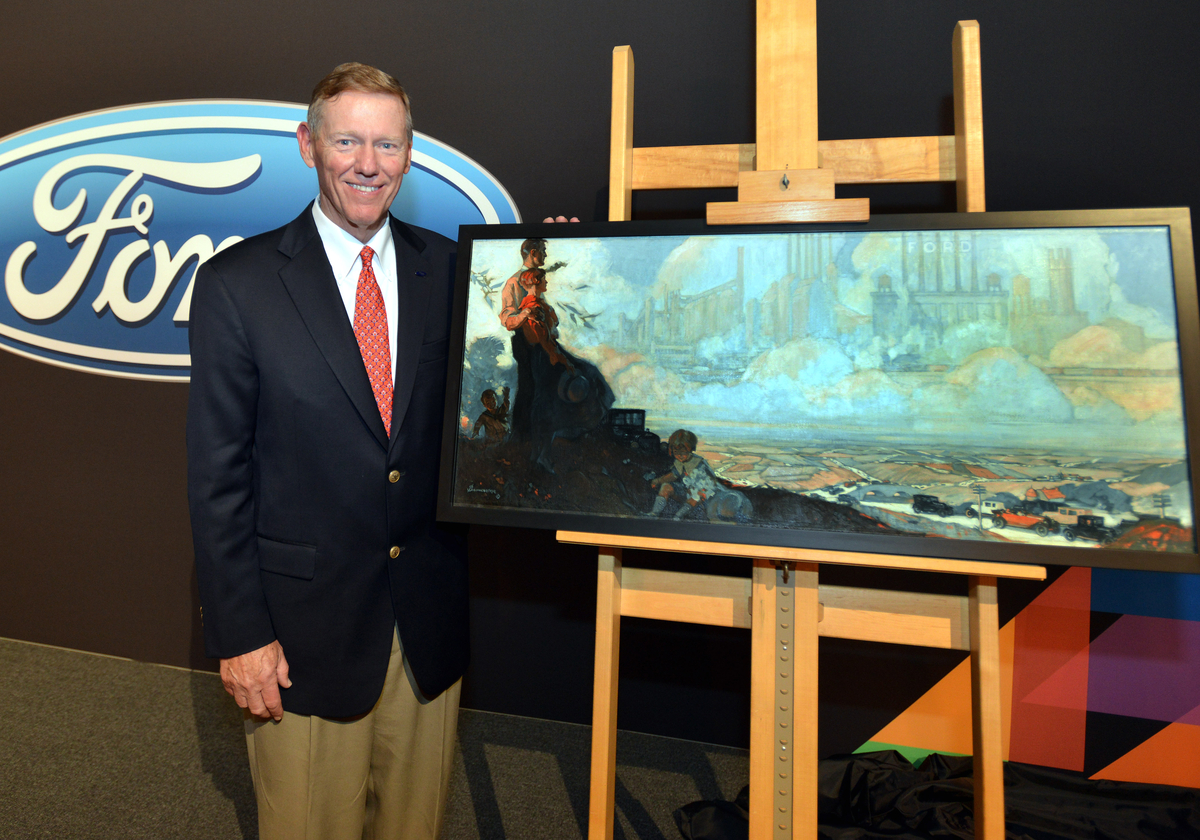

Mulally didn’t create a new value proposition for the company. Instead, he found the original one written by the company’s founder, Henry Ford.

When Ford started, owning a car was reserved for the wealthy. Most people couldn’t afford to own a vehicle. Henry Ford’s mission was to change that and to “open the highways to all mankind.”

Mulally believed in this value proposition so much that he hung it in the hallway of Ford’s headquarters and handed out copies to Ford executives. And all future product development would be weighted against the promise made in this value proposition. It may have been a value proposition created 80 years ago, but Mulally loved its message and what it promised. (If you haven’t caught a theme of this article, it’s that Mulally sticks to a plan).

In keeping this value proposition alive nearly 100 years later, Mulally ensured that Henry Ford’s DNA and original vision would guide the company.

The takeaway here would be to truly understand your company’s value proposition and let it guide your future product development.

Conclusion

Starting a company and building it into a success story is quite a challenge, but taking over a company that’s damaged and returning it to the former glory days is a unique challenge and one that few modern executives have accomplished.

So, what was the method to Mulally’s success?

Was it his 12-hour workdays?

Nope, plenty of executives work hard and don’t deliver results.

Was it luck?

Anything but luck! Entering a company losing billions of dollars every year, then the Great Recession two years later and turning that same company into 19+ consecutive profitable quarters isn’t luck.

Mulally’s ideas weren’t new. Instead, it was sticking to those business fundamentals – teamwork, business plans, and delivering useful products that made Ford successful.

It was Mulally doing extensive research to understand Ford’s issues, and creating a plan (and sticking to it) and delivering results against that plan. It was the brutal honesty of being an outsider and assessing a company with a fresh eye. His inexperience in the auto industry but strong management skills are what made this turnaround special.

And it was Mulally’s commitment to a plan and people. As an engineer, he wasn’t expected to be a people-person. But he was – personable but tough. People who have spoke with Mulally say that he “makes you feel like you’re the only person in the room”. This kindnes

source https://blog.kissmetrics.com/business-and-leadership-lessons-from-one-of-americas-top-turnaround-executives/

No comments:

Post a Comment